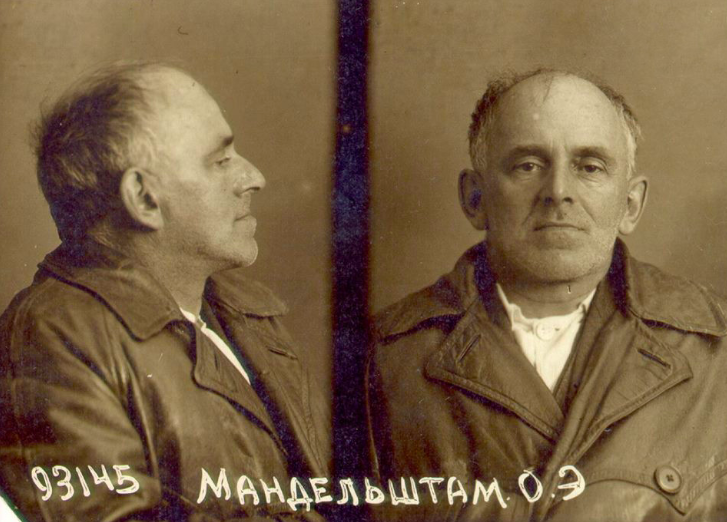

It’s 70 years since the death of Stalin. I wrote about the anniversary, and its current echoes, for The Bulwark. But here’s a postscript: a haunting poem about Stalin written in 1933 by the great Russian-Jewish poet Osip Mandelstam, which played a role in his eventual arrest and imprisonment in the gulag (where he died in 1938). Even apart from its tragic significance, it is a superb and remarkable document of the Stalin years. In twelve lines, it captures the essence that takes volumes to explain: the overriding climate of fear and trembling in Stalin’s USSR; Stalin’s absolute dominance of public space; the larger-than-life inhumanity of his presence, both animalistic and diabolical; the grotesque cravenness of the Stalin-era Soviet elites; and, finally, the centrality of brute force and carnage.

Here’s the Russian text:

Мы живем, под собою не чуя cтраны,

Наши речи за десять шагов не слышны,

А где хватит на полразговорца,

Там припомнят кремлёвского горца.

Его толстые пальцы, как черви, жирны,

А слова, как пудовые гири, верны,

Тараканьи смеются усища,

И сияют его голенища.

А вокруг него сброд тонкошеих воҗдей,

Он играет услугами полулюдей.

Кто свистит, кто мяучит, кто хнычет,

Он один лишь бабачит и тычет.

Как подкову, кует за указом указ: Кому в пах, кому в лоб, кому в бровь, кому в глаз. Что ни казнь у него—то малина И широкая грудь осетина.

There are several English translations, none of which I found satisfying for various reasons. Free verse translations of rhymed/scanned poetry rarely “work” in my view, since they fail by their very nature to capture the dynamic and quality of the original. (Free verse can be brilliant but it is a fundamentally different animal from traditional verse.) The ones that do rhyme and scan tend to be clunky.

I’ve been trying my hand at verse translation in the past couple of years. Here’s my version of the Mandelstam “Stalin epigram.” (Many thanks to my friend Tanya Golubchik for her suggestions on how to make it better.)

With no land felt beneath us, we live day to day; Our speech barely carries ten paces away, Each half-snatched conversation remembering The highlander up in the Kremlin. His fingers are greasy as overfed worms, And final as cast-iron weights are his words; Cockroach whiskers are laughing and winking, And his boot tops are gleaming and twinkling. There’s a rabble around him of chiefs with thin necks; He plays with half-humans he’s got at his beck: Some mewling, some whimpering, some hissing; He goes poke! he goes boom! and they listen. Like horseshoes he drops one by one his decrees: To the groin, to the head, to the eye, to the knees; Every killing’s a sweet celebration, And stands tall the broad-chested Ossetian.

Verse translation is always hard. Translating Mandelstam is perhaps especially hard, because his language is often deliberately abstruse, coded and full of allusions. The last two lines of the Stalin epigram pose an especially tough challenge. The next to last line, which literally translate as every execution is raspberries, has an uncapturable dual allusion: the phrase ne zhizn’, a malina (literally “it’s not life, it’s raspberries”), which means, essentially, “this is the sweet life”; and malina (“raspberries”) as slang word for the criminal underworld, or a criminal gang. “Every killing’s a sweet bowl of cherries” would convey the first meaning quite well, but still lose the second.

The last line, I shirokaya grud’ osetina (“And the broad chest of the Ossetian”) is even more mysterious. In Russian, it’s grammatically weird, suggesting that each execution is “a bowl of raspberries” and an Ossetian’s broad chest. What does this mean? That Stalin enjoys executions as much as he enjoys a broad Ossetian chest? Or (more likely) that the broad Ossetian chest is Stalin’s own, an embodiment of his towering machismo? I’m well aware that my version is inadequate. I tried, though.

As a bonus: a great 2010 essay by the Spanish poet José Manuel Pirieto in the New York Review of Books about the Mandelstam poem, its history, and Pirieto’s own translation of it.